‘Designing a World Without Limits’

朱婧绮 中国人民大学附属中学通州校区

Introduction

As one of Shenzhen’s key cultural landmarks, the Shenzhen Museum not only displays the city’s history and development but also serves as a hub for promoting culture and educating the public. However, for visually impaired visitors, the museum’s wealth of visual information can be difficult to fully experience, creating significant barriers to their cultural engagement. To help bridge this gap, I participated as a group leader in the ASDAN Volunteer Information Accessibility Program. In this role, I accompanied a visually impaired friend during a tour of the Shenzhen Museum, aiming to enhance her experience by providing support and detailed explanations of the exhibits.

The Power of Touch

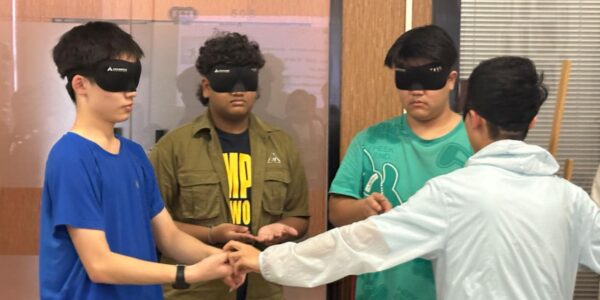

During the visit, I became keenly aware of the challenges that visually impaired individuals face in a museum setting. As the group leader, alongside my co-leader, we greeted a young woman who was completely blind. She was strikingly beautiful, with a high nose and well-defined features, her long hair tied in a confident ponytail. Our supervisor mentioned that many visually impaired individuals still take great care with their appearance—this young woman, for example, wore glasses to cover the visual imperfections of her eyes because of her love for fashion. I was struck by a deep sense of empathy, imagining that if she were sighted, she would simply be a cheerful, stylish girl who wanted to see the world like the rest of us.

With that thought in mind, we began our tour in the history exhibit. Most of the items were artifacts, images, and models. Since she couldn’t see the exhibits, I described each one in detail, explaining the shape, color, material, and the historical context behind it. When we reached a set of spear replicas that visitors were allowed to touch, I guided her hand so she could feel the shape of the spears. In this way, she didn’t just hear about the artifacts—she could physically connect with them.

Throughout the tour, I wasn’t just her eyes but also her guide. We would often pause so she could ask questions, such as where the artifacts came from and what they were used for. I did my best to answer in ways that she could easily understand. Through this interaction, I realized that while visually impaired individuals may not see the world as we do, they are just as curious and eager to explore. They want to experience and understand the richness of the world in their own way.

Reflections

Visually impaired individuals have diverse needs when it comes to cultural experiences. After the tour, we returned to the classroom and interviewed one of the visually impaired participants, Brother Mengqi, to get his feedback on the museum. He raised several issues, such as the lack of tactile pathways for the visually impaired, the long distance between the parking lot and the entrance, the absence of touchable exhibit replicas, and the fact that the guide’s voice was too soft to hear clearly.

Based on his feedback, our group concluded that cultural institutions like museums could significantly improve the experience for visually impaired visitors by offering specialized tours, tailored routes, and more tactile opportunities. Modern technology, such as audio guides and 3D-printed tactile models, could also help enhance their understanding of the exhibits.

However, these needs are still largely unmet in many cultural venues. Although some museums have accessibility features, these are often just the basics. What truly enhances the experience is innovation and investment in services and content that cater to the visually impaired.

A Hope for the Future

Following this experience, our group chose to research policies on supporting people with disabilities in China as part of our project report. In recent years, China has made significant progress in safeguarding the rights of people with disabilities, introducing various laws and regulations to protect their basic rights and improve their quality of life. However, there are still gaps in policy implementation, particularly in the cultural sector, where the needs of the visually impaired are often overlooked.

Through this experience, I realized that beyond improving policies, we need greater social awareness and participation. While policies mention improving cultural services for people with disabilities, many cultural institutions lack a deep understanding of their needs. This leads to limited services and a diminished cultural experience for the visually impaired. Going forward, it’s crucial that policy-making involves more input from people with disabilities, ensuring that their real needs are met through practical and targeted measures.

Conclusion

My experience accompanying a visually impaired person through the Shenzhen Museum opened my eyes to the fact that culture belongs to everyone, and the visually impaired have just as much right to enjoy its richness. As members of society, we have a responsibility to help break down the barriers they face, allowing them to experience culture in new and meaningful ways. In the future, I hope to see more cultural institutions recognize and address the needs of visually impaired visitors, through improved infrastructure and innovative services. Let’s work together to create more opportunities for them to engage fully with the world and share in its beauty.